Surrender

Patience may just lead to perfection.

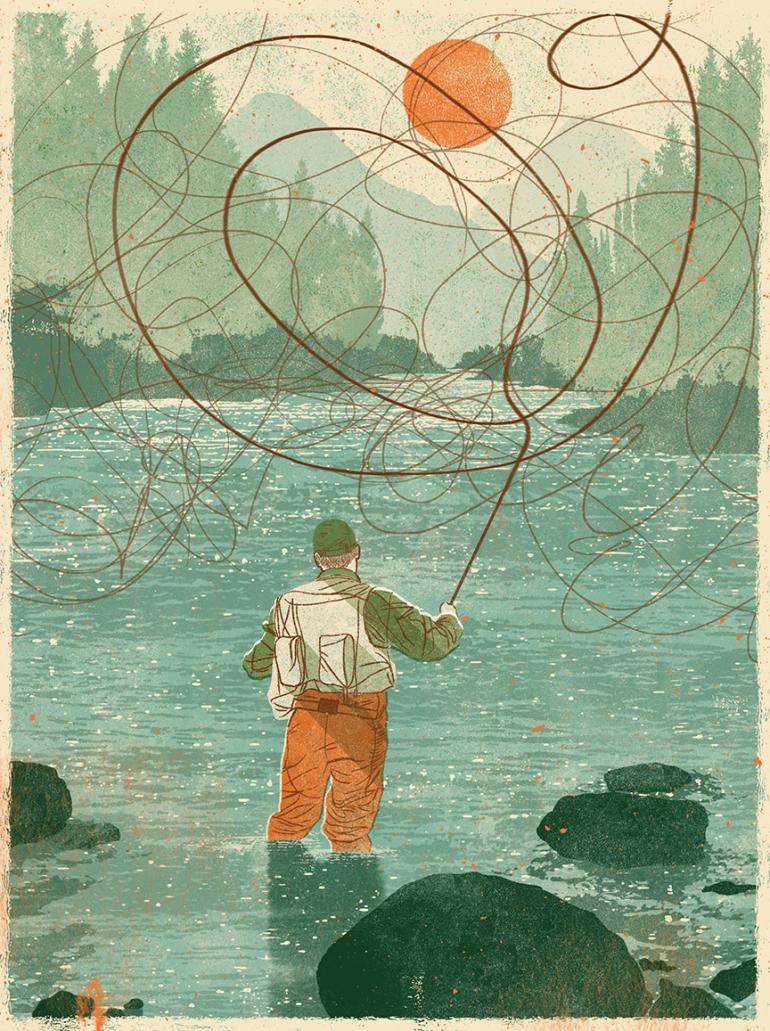

When I first observed spey casting, it looked like a man waving in surrender, or perhaps a horsetail swatting flies off its ass. There is nothing graceful about either image.

As any local knows, there is little out there that can match the beauty of a first-rate fly cast. I’m sure the gurus will tell you that the beauty is in the execution—that casting is in the hands of the fishermen. That’s wrong. The deeper beauty of a fly cast lies in one’s complicit resignation to defeat, as if with each frustrated cast the fisherman admits that life is a crapshoot.

Perfection in fly fishing is rare. How often do we really lay a perfect cast—gently unrolling, just in front of a log, mending in time to prevent drag but keeping the fly in a seam long enough for a 20-inch trout to slam the bug—then set the hook with the perfect synthesis of authority and delicate, compassionate tension? It happens, but not often. It’s this frozen moment of perfection that keeps us coming back. But before achieving such perfection, we must confront the idea that like the last 40 casts, the next will probably be a failure, too.

There is even less perfection in the catch—a fish takes the fly, you set the hook, then dance. The fish tries to lead but soon anchors down under a rock. You extricate the fish with gentle tugs like a river puppeteer, leading the fish against the current until it takes over and leads you a hundred yards downstream. Then you have to land the thing. Most people use a net. The pros use a net and a butler to wield it. Try landing a fish without a net, the hard way.

I am an amateur. Perfection was always the last thing on my mind. I can’t tell you how many thousands of casts I wasted just trying to keep my fly on the water, relying on the odds instead of manipulating them. It was arduous, but I learned how to catch fish the ugly way. It wasn’t until last spring that I realized I’d become a real fly fisherman—a master of the fly rod.

It happened on a trip to the Adirondacks in New York, when my friend and I stopped at Oneida Lake to catch some walleye for a campfire dinner. I waded into the waves and began casting randomly into the open expanse. I have to imagine that saltwater fishing is the loneliest form of fly fishing—just staring out into the endless water, wondering how in that space a fly would ever find its way into a fish’s mouth. It wasn’t long before a crowd had drawn around me. It pissed me off at first, because they were ignorantly standing in my back cast. Whose lip would rip that day?

But I soon realized that I wasn’t just an oddity in the realm of spin casters. They were actually admiring my casting. For years I had simply done it automatically, always focused on the target and the fish. That day I took the time to look up at the line coiling and firing, arcing and diving. It was beautiful.

The sun set on the lake and the walleye moved in to feed on shiners. There were millions of them, each one reflecting the moonlight. I began to wonder how a fish could ever pick my fly out of so many options. Still, I got one tug—not perfection, but an adventure nonetheless.

I don’t care if I’m refused a take on a strong cast. Humans love to organize the chaos—it gives us a false sense of control. If I am refused a fish on a perfect cast, I start questioning my karmic dividends. (Shouldn’t have given that Sunday driver the finger last week.) Fishermen factor in everything, and it probably wouldn’t be a stretch to find a karma-level column below a fisherman’s log of water temperature and moon phase.

Fishing, like hunting, is predatory. Perhaps that’s the key: by fishing we enter into the eternal cycle of predator and prey—we give up our privileged skybox on nature’s sideline. In this element there is no failsafe or guarantee. We surrender the comforts of home; we surrender our pride; we surrender the fish back to the river. Most of all, we surrender our souls to the experience. Fishing requires nothing less than that. Keep that in mind the next time some smug guide rows by in his airbrushed $10,000 dinghy. If the gurus were polled, patience or dedication would be the top lessons learned from fishing. For me, the lesson is always humility.

Common complaints are that fly fishing is too hard. Not so—it may be hard to get a role in a Robert Redford film, but it’s not too hard to catch a fish. I remember the first fly cast I made in the backyard with a borrowed rod, trying to hit the pin in a horseshoe pit. It took two tries. Approaching perfection is hard, but catching a fish on a fly rod is relatively easy once you’ve got a handle on patience and dedication. Fishing is too dynamic for hard and fast rules—water washes over stone, after all.

It might not be such a great idea to take the advice of an amateur. It seems paradoxical. I could have saved thousands of hours on the river had I not learned things the hard way. But if the river is where you want to be, there is no wasted time. Have the courage to go out and look like an amateur all day. This is what separates those who triumph from those who fail: those who fail are afraid to do so. Surrender.