Trains and the Treasure State

No form of transportation has had a more profound impact on the Treasure State than the train.

Like the rest of the American West, the history of Montana is closely linked with railroads; trains provided the most effective and reliable means of shipping goods, services, and people around the vast new countryside. The first tracks across Montana were envisioned by the Northern Pacific Railroad, which wanted to build a rail line linking the Great Lakes region to the Portland-Seattle area. Congress approved the charter for the NP in 1864, the same year the first major gold strike in Montana occurred. Within 10 years NP survey crews were pushing their way into Montana Territory, charting a course for the railroad along the Yellowstone River, but the Northern Pacific would not be the first railway to transport the Treasure State’s riches.

In 1869, the first transcontinental railroad, stretching from Omaha to Sacramento, was completed near Corinne, Utah, by the Union Pacific and the Central Pacific Railroads. The symbolic golden spike driven into the final rail was tantalizingly close to the gold fields of Montana, and Mormon investors in Utah like John Young (son of Brigham Young) saw an opportunity to beat the Northern Pacific into Butte, fast becoming the center of mining operations in the region. In 1871 Young and his fellow investors founded the Utah Northern, a narrow-gauge feeder line which would run north from the transcontinental railroad into Montana mining territory. The Utah Northern would be absorbed by the Union Pacific by 1878, and renamed the Utah and Northern-Union Pacific line; the first train rolled into the station in Butte on December 26, 1881.

The Utah and Northern may have beaten the NP to gold country, but the financial depression that came to be known as The Panic of 1873 was more to blame than geography. Railroad construction came to a virtual standstill across the entire West during the 1870s, prompting the Bozeman Times to note in 1876 that, without rail service, Montana was a “dull monotonous Territory, cut off from the world and civilization.”

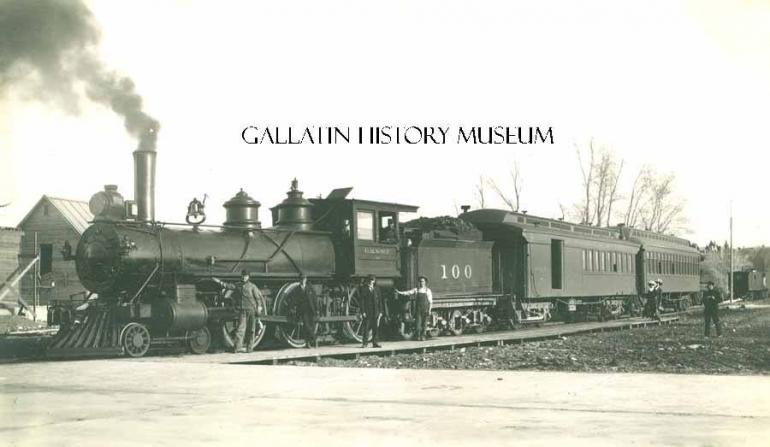

The Northern Pacific reached Bozeman by the early 1880s. Crews laid tracks west along the Yellowstone River, founding the towns of Billings and Livingston along the way. A tunnel was blasted through the Bozeman Pass, and the route continued through the Gallatin Valley, up the Missouri River to Helena, and over the continental divide. Crews worked eastward through Washington and Idaho, and then along the Clark Fork River; the NP’s northern transcontinental route was completed at a “last spike” gala near Gold Creek, Montana, on Sept. 8, 1883, but competition was soon to follow.

Jim Hill’s Great Northern line was built between Minot, North Dakota, and Everett, Washington, from 1887-1893. Rail centers like Great Falls and Havre were born as a result, and the “High-Line” owes its name to the Great Northern tracks skirting the Canadian border. Hill’s crews laid tracks through Marias Pass, at the southern end of Glacier National Park, resulting in a transcontinental rail route that Hill, known as the “Empire Builder,” boasted was “shorter than any existing transcontinental railway, and with lower grades and less curvature.” A few years after completing the Great Northern route, Hill also took control of the Northern Pacific.

The Burlington line entered the scene in the early 1890s, boosting the economy of the Billings area with its Laurel-to-Denver route. The Montana portion of the “Milwaukee Road” was completed in 1909. By 1916, the Milwaukee ran electric trains from Harlowton to Avery, Idaho; the 440-mile-long stretch was once the largest section of electrified main line in the world. The driving of the last spike for the Milwaukee line also marked the end of main railway line construction in the state.

Railroads brought people to Montana to stay. Along with the towns and cities the railways created along their routes, such as Livingston and Billings, the railroads offered land. Rail companies like the NP had received huge federal land grants when building their lines; the NP owned about one-seventh of all the land in Montana early in the 20th century.

The western lands possessed by the railroads were sold to people unable to obtain free land through the Homestead Act. Railroads advertised this acreage heavily in Europe and in the midwest and eastern states, and many people were lured to the Treasure State with the promise of cheap, bountiful land. The NP sold much of its Montana land by 1917 for up to $8.56 an acre.

The railroads also helped to develop one of Montana’s main “modern” industries, that of tourism. Rail-based tourism income averaged $500,000 annually in the state during the first decade of the 20th century. The NP was routing tourists through the Gardiner entryway to Yellowstone Park heavily in the early 20th century. The Milwaukee spurred tourist traffic up the Gallatin Canyon and into the Park from its beautiful railhead hotel, the Gallatin Gateway Inn, built in the 1920s, and the Great Northern steered tourists into Glacier National Park.

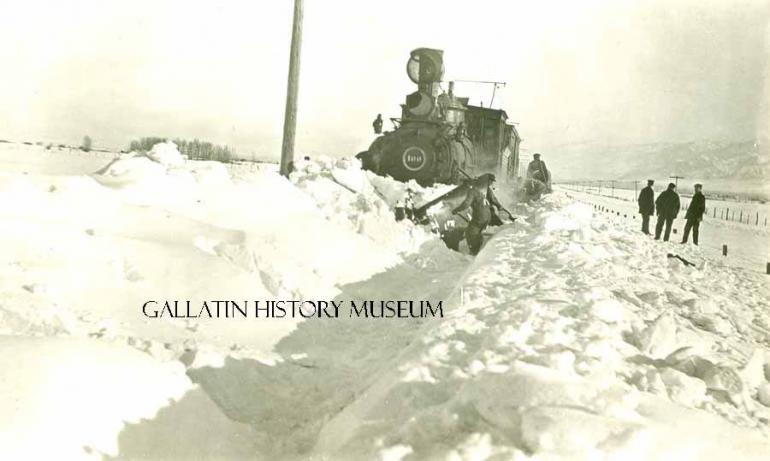

The 1970s saw a decline in passenger rail service to the state. Trains got less business as the interstate highway system was completed, and Amtrak passenger service in Montana is only available on the “Empire Builder” route, Jim Hill’s original Great Northern passage, itself currently threatened by proposed federal budget cuts. Trains are still essential to Montana’s commercial, industrial, and agricultural interests, however; roughly three to four thousand miles of track remain in use in the state.

Trains have left their historic mark on the state, and will continue to do so as long as they provide the transportation needed to help Montana’s economy grow. Montana towns like Dillon, Harlowton, and Billings owe their names to railroad men, and historic depots like those in Livingston and Missoula serve as reminders of the train’s legacy in Montana just as surely as the sound of a locomotive’s whistle in the Big Sky night.

Railroad Money

The Panic of 1873 slowed railroad construction in the West for nearly a decade; ironically, the nationwide depression was itself triggered by the race to lay rails in the frontier.

Politics and money went hand in hand with western railroad expansion. Capitalists and government officials alike had ideas for a transcontinental railway by 1849, as the California gold rush began in earnest. The Civil War put the brakes on transcontinental rail construction, but not on the planning. In 1865, the Union Pacific began to work its way west from Omaha, as the Central Pacific worked eastward from Sacramento, in a race to see which corporation could lay the longest stretch of track.

The race between the railroads was for profit, not for glory, and it marked a scandalous period in “creative” American finance; railroads earned their place on the Monopoly board. Both the Union and the Central Pacific were awarded government subsidies based on the amount of track laid, and both corporations padded their earnings through tricky bookkeeping and “dummy corporations.” The UP’s Credit Mobilier and the CP’s Credit and Finance Corporation were simply subsidiary corporations owned by the railroads’ stockholders. Expenses were doubled, and even tripled, by both outfits, in the scheme to boost profits.

By 1869, when the transcontinental line was completed, the jig was up: the Credit Mobilier’s hijinks came to light in the national press, and a subsequent Congressional investigation revealed that the entire GOP leadership had been bribed in order to enable the enterprise. The Central Pacific’s Credit and Finance Corporation escaped public scrutiny and Congressional fallout with an old fallback: their records were destroyed in a fire.

While the CP and the UP made millions in subsidies, the next transcontinental line would make its profits with land. The Northern Pacific was given huge land grants by the U.S. government to build their northern route across the continent—the 20 sections of land for every mile of track in Oregon and Minnesota and 40 sections in the territories between the states (44 million acres) was the largest land grant in American rail history. 17 million of those acres were in Montana Territory, making the NP the largest private landowner in the state.

The exposure of tricky railroad financing had made the western rail race more difficult, however, and in an effort to raise enough cash to complete the NP line, Philadelphia banker and NP booster Jay Cooke, whose bank agreed to finance NP construction in 1870, “overextended” his assets, and the bank collapsed, touching off The Panic of 1873. All western rail construction halted as a result of the depression for four years or more.

The Great Northern was the last transcontinental railroad built in the U.S., but James J. Hill wasn’t able to get land grants out of the deal. The Panic of 1873 had slowed the government’s enthusiasm in any form of “venture capitalism,” but Hill did harvest some government financing, completing the Great Northern as another major depression, the Panic of 1893, put the brakes on the American economy.